Years ago, when I had just started to take design a bit more seriously, I envied designers that produced amazing visual designs or incredibly slick animations. I envied the front-end developers because they could turn designs into interactive websites. I envied illustrators that could draw awesome icons.

Compared to them, I felt mediocre and I was frustrated because of it. You see, I never specialised in anything. Since I was a child, I had a habit of putting things together and create something out of that. I saw things differently from others. Where everyone else saw a cardboard box, I saw a cool military jeep that I could create out of it.

But that was different. Or at least, at that point I thought it was. I was studying management and economics at a local university when I turned my hobby into a small business that was enough to get by. I was doing proper UX/UI design work for clients worldwide. Looking back, I now realise I was doing well. But that didn’t mean much to me. People wouldn’t hire me to draw pretty illustrations and they wouldn’t hire me to do front-end development stuff. They hired me to bring their brands to life (yes back then I did that sort of work too) and design their websites. They hired me to design user experiences and do pretty much everything design-related for them—including building and deploying the websites I designed for their projects. Believe it or not, that only fueled my frustration.

These would be the skills that I had then. Enough of each to get by, but not really specialised in anything. At least that’s how I felt at the time.

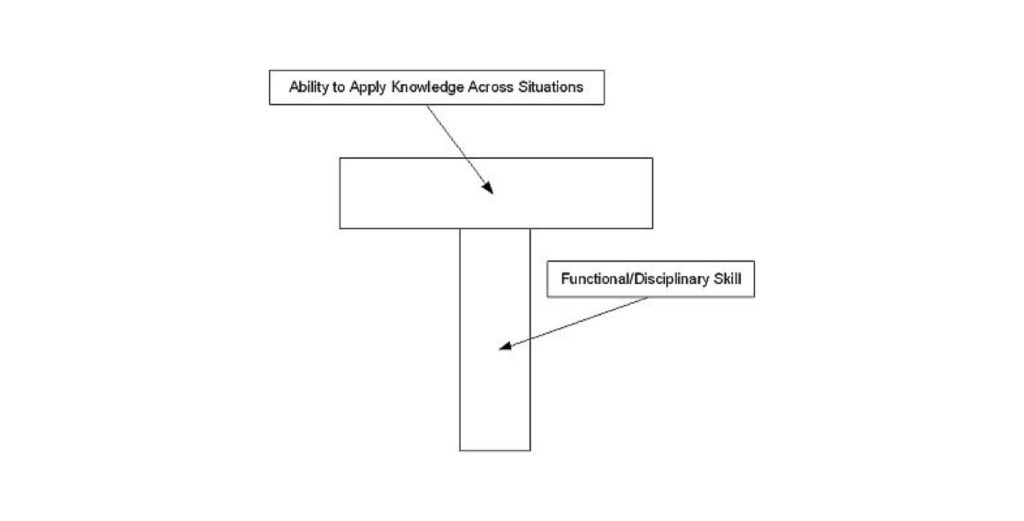

T-shaped skills

Then, one day, I stumbled upon the “T-shaped skills” concept. I had never heard of anything similar before. Let’s take a look at what exactly it means: Having skills and knowledge that are both deep and broad1. I decided to dig deeper and I learned that generalists (people with such skills) are in high demand at some of the best companies. Companies that solve tough problems using the so-called design thinking. That was the first time that I saw my lack of specialism as something that could potentially be good. Looking back now, it seems that at that moment, I made a subconscious decision to become a generalist. A while later it became clear to me that being a generalist is an amazing thing (and that I was a generalist already anyway) so I made a conscious decision to specialise in that.

The thing is, generalists don’t necessarily have average skills all around. The name “generalist” tends to imply that but it’s not true. Once I decided to become a proper generalist I decided that UX/UI would be my main skill so I would put most effort into improving that. But being a generalist means that I put a lot of effort into picking up other, complementing skills. Web design, native apps design, visual design, front-end development, design-thinking, prototyping etc. They would all get an equally important part in acquiring and developing skills. And it’s not just acquiring skills for the sake of it. It’s acquiring skills with an intent to use them or in most cases even acquiring skills by using them before acquiring them (learning by doing)—which often requires improvisation.

My goal changed from naively striving to be the best at everything (and wasting energy and time to get there) to making small and systematic steps towards becoming the most complete designer I can be. Since I consciously started working on specialising as a generalist, my skills set is more complete. I know that my illustration and animation skills are still quite basic, but so far, they were always good enough. That’s what being a generalist means to me: knowing how to apply the skills you already have and pick up new ones when needed and apply them immediately.

Why is being a generalist a good thing?

People possessing these [broad] skills are able to shape their knowledge to fit the problem at hand rather than insist that their problems appear in a particular, recognizable form. Given their wide experience in applying functional knowledge, they are capable of convergent, synergistic thinking2.

Let’s think about a real-life scenario. We have two teams:

Team A: Sam is a UX/UI designer with an interest in front-end development and product design/management. Other members of the team are John, a full-stack web developer and Scarlet, a product manager. John has a particular interest in UX and design in general. Scarlet, the product manager, has some UX background and loves doing UX research and customer development.

Team B: Allison is a UI designer. She likes to create pretty things and hates when other people make her push pixels around. Emma is a UX designer, she loves creating wireframes and prototypes. She’s comfortable with letting Allison take over from there. Peter is a product manager, he loves coming up with ideas for products and thinks that’s his responsibility. Eric is a full-stack developer as he does both: back- and front-end development.

The need for T-shaped skills surfaces anywhere problem solving is required across different deep functional knowledge bases or at the juncture of such deep knowledge with an application area.

— Leonard-Barton

Research suggests, that people who have broad skills communicate and work with others better. It makes sense: because Sam from team A knows a bit about front-end development, it’s much easier to talk to web developers and explain what needs to be done. The same goes the other way, John—team A’s full-stack developer knows a bit about design so he can suggest improvements the designer might have missed. Team A is a small squad that has the skills and the mentality required to find out what needs to be built and then go on and build it. Put a good product development process on top of that and the chances of success rise dramatically.

Team B on the other hand, is much more likely to have communication issues. Designers that aren’t comfortable getting feedback early and often can’t function in teams that need to move fast. Product managers that think that coming up with product ideas is solely their responsibility are hard to work with because they hate it when people question their ideas. Allison, the UX designer likes the wireframing and prototyping part but doesn’t have a habit of seeing products through to the end. Eric, the team B’s full-stack developer is the person that comes closest to being a generalist. But it’s not enough.

Conclusion

I’m not saying that everyone should aim to become a generalist. There’s room for specialists in product development teams too. But there needs to be the right balance of the two. What I am saying though is that being a generalist is fun. Having a holistic overview of the product development process and see things through to the end. Making sure that things get built as they were intended and learn how to improve with the next iteration at the same time. I don’t really think it’s just about acquiring and using different skills—It’s a mentality.

1 comment